Defining a Problem:

Which user needs are not being met?

Define:

What does it mean to "Define a Problem" in design thinking?

During the Empathize phase we were gathering data and building a picture of things. We asked people about their experiences in an open ended way and without a specific direction in mind. You now have a lot of data about user needs, so, what do you do with it?

Our goal in the Define stage is to understand how everything we learned about users and thier needs fits together.

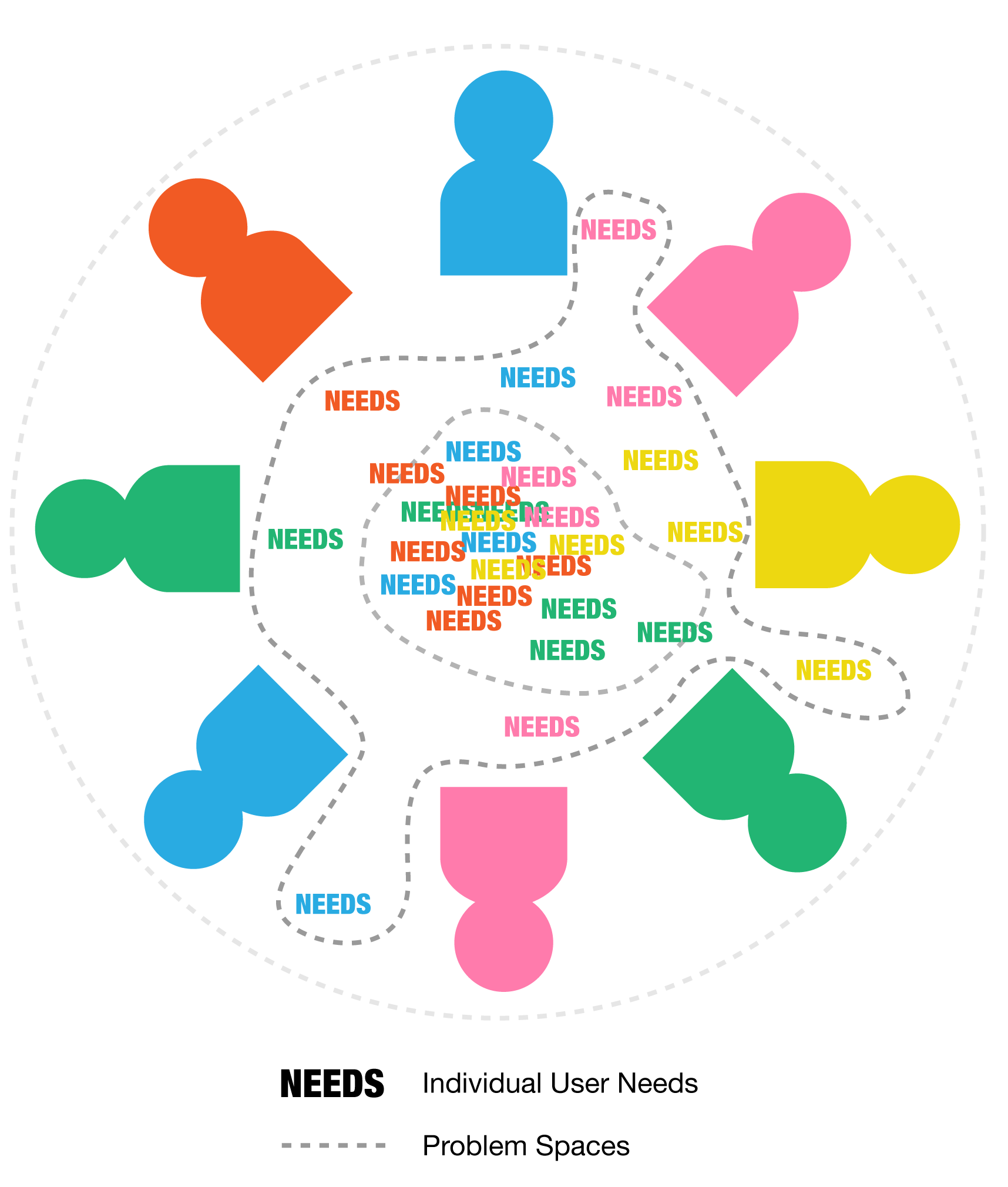

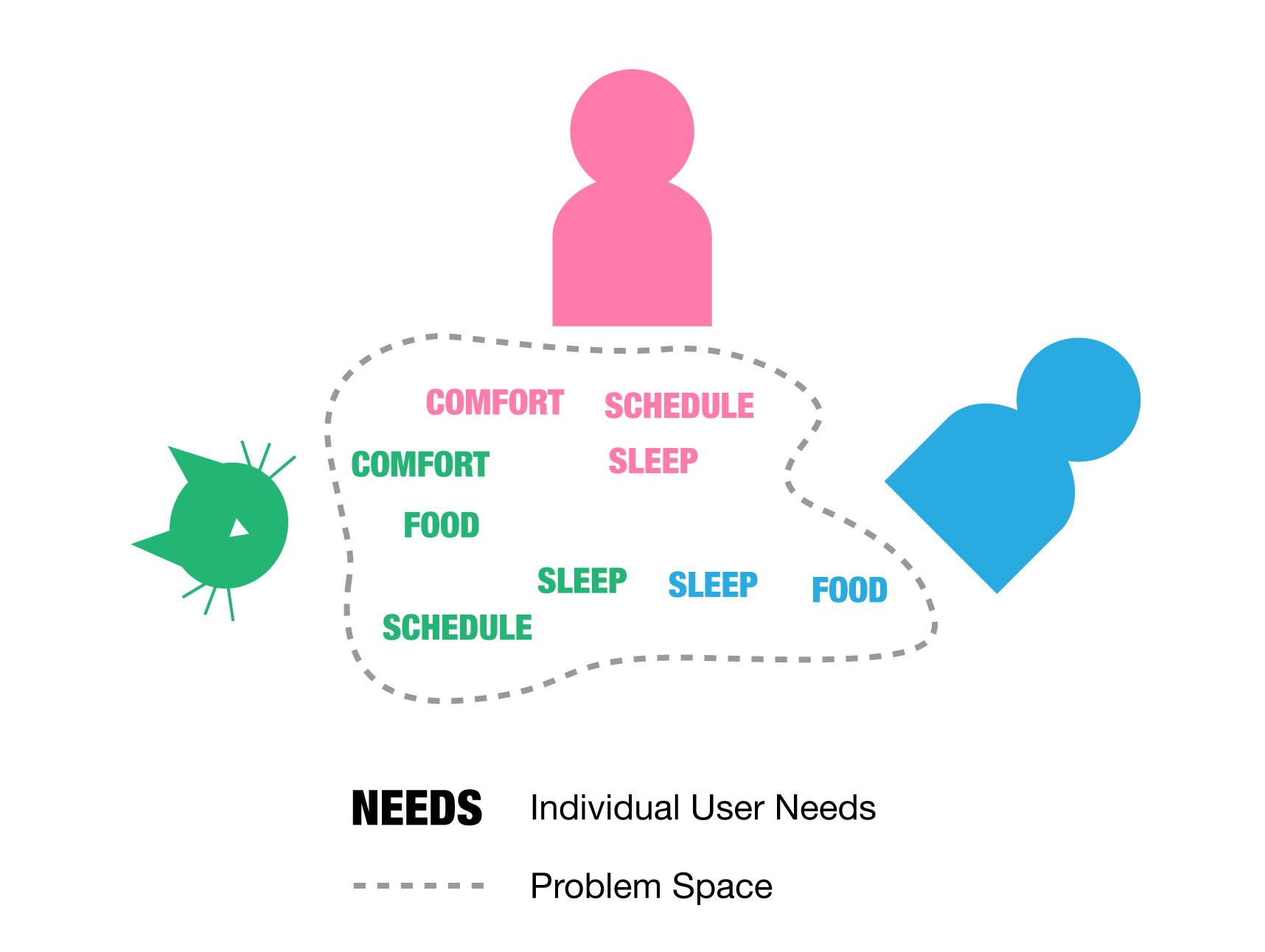

The problem space defines all of the interconnected user needs that we are trying to satisfy.

A problem statement is a question we write that leads us towards creating the solution space.

If we can find genuine connections between individual user needs, we can enlarge the problem space. A broader problem space can result in more pwoerful solutions.

Define the problem:

A simplistic problem statement is something like how can we increase sales of our catfood?

A slightly more insightful problem statement might be:

how can we get cats more interested in our food?

One problem statement is a dead end. The other gives us something to think about. It "defines" the problem in a way that we can start to do something about it, because it considers the users' needs (what do cats like?)

An ever better problem statement is one that looks at the problem space from a whole new perspective. We want to see the connections between users and their needs in ways that nobody has before. We call that "re-defining" the problem.

Re-define the problem:

The classic designing thinking example of "redefining the problem" is the pale blue dot, a photo that gave humanity a new perspetive.

Today the world feels small. We have mass media, the internet, cellphones, globalization, online shopping, next day shipping. Virus that spread to every corner of the globe in a few months.

But last century the world was still a very big place in many ways. What happened on the other side of the planet seemed like it had nothing to do with us. People could ignore problems in other places. Pollution in one country did not impact another country. Resource scarcity was unthikable. The earth was a big, boundless, and ever providing.

And then this photo was taken from the moon in 1968:

"Earthrise" by William Anders, Dec 24, 1968

Every single thing in the world. The stuff of every person who ever lived, died, and perhaps who will ever be born is, and ev everything we will ever be given to do what we want to do is visible in a single photo. Or,

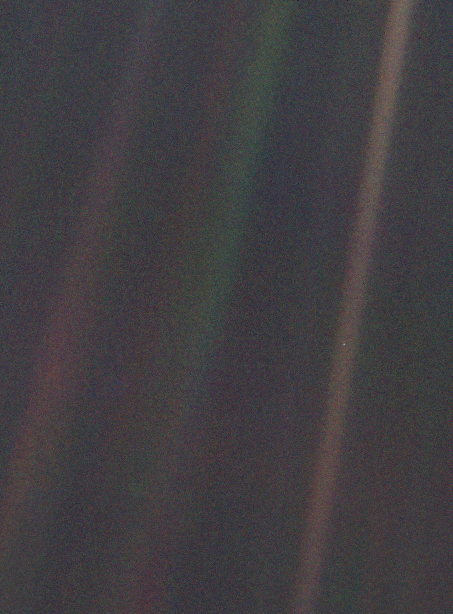

There is perhaps no better demonstration of the folly of human conceits than this distant image of our tiny world. To me, it underscores our responsibility to deal more kindly with one another, and to preserve and cherish the pale blue dot, the only home we've ever known.

- Carl Sagan

You can listen to the whole quote here: Carl Sagan's Pale Blue Dot

When people saw this photo, they stopped seeing their problems and other people's problems, as local problems, and started to see themworld problems. It re-defined the problem space.

Back to cats:

Let's talk about cat food, and re-defining the problem of cat food. Consider this cat food commercial from the 1980s.

or this one

These commericals are selling to the cat. They brag about about flavour. They promise that the cat loves the taste, maybe hint at health claims, and that's about it.

Can a photo like this re-define the problem of "how can we get cats interested in our food?"

A whole new point of view on catfood.

What might this photo ask? How can it re-define the problem? Maybe it suggests we should re-define the problem again:

How can we get cat owners more interested in our food.

And if you look at cat food advertisements from today, that they really are selling to the owners:

This commerical promises to "maintain a cats inquisitive nature" - for who's benefit? The cat's or the owner's? (hint: curious cats are cute, but curiosity killed the cat). download

and this one

This commerical doesn't even try to "sell to the cat." It isn't even about the food! download

Without spending too much time on catfood, notice that catfood trends - low carb, no grains, and especially no corn, high protein, pea-protein, organic, holistic, all natural, local, vegan, tend to follow human food trends? That is a "problem re-definition" for sure.

The Atlantic - The Humanification of Pet Food Is Nearly Complete .

What we do matters and has impacts

Catfood is a good example because it is a clear example. But as designers we might be dealing with things bigger than whether or not Purina outsells IAMS.

We might be dealing with problems that really impact people's lives. It might impact their access to services, to happiness, to equal chances.

Example Problem:

In order to demonstrate the design thinking process, I am going to introduce an example design problem. For these lessons, we will follow the exampl problem as we learn to tools to solve it.

Imagine a household consisting of three users, who we learned about with Empathy gathering exercises:

- Cleo the cat

- Jasmine

- Karl

But there is a crisis! Every morning at 5:30am, Cleo the cat has been crying loudly to be fed. This wakes Jasmine up too early. Karl tried leaving out extra food, but Cleo eats it all and vomits. WHAT WILL WE DO?

Use these tools to define the problem:

- Personas

- Journey Maps

- Coding

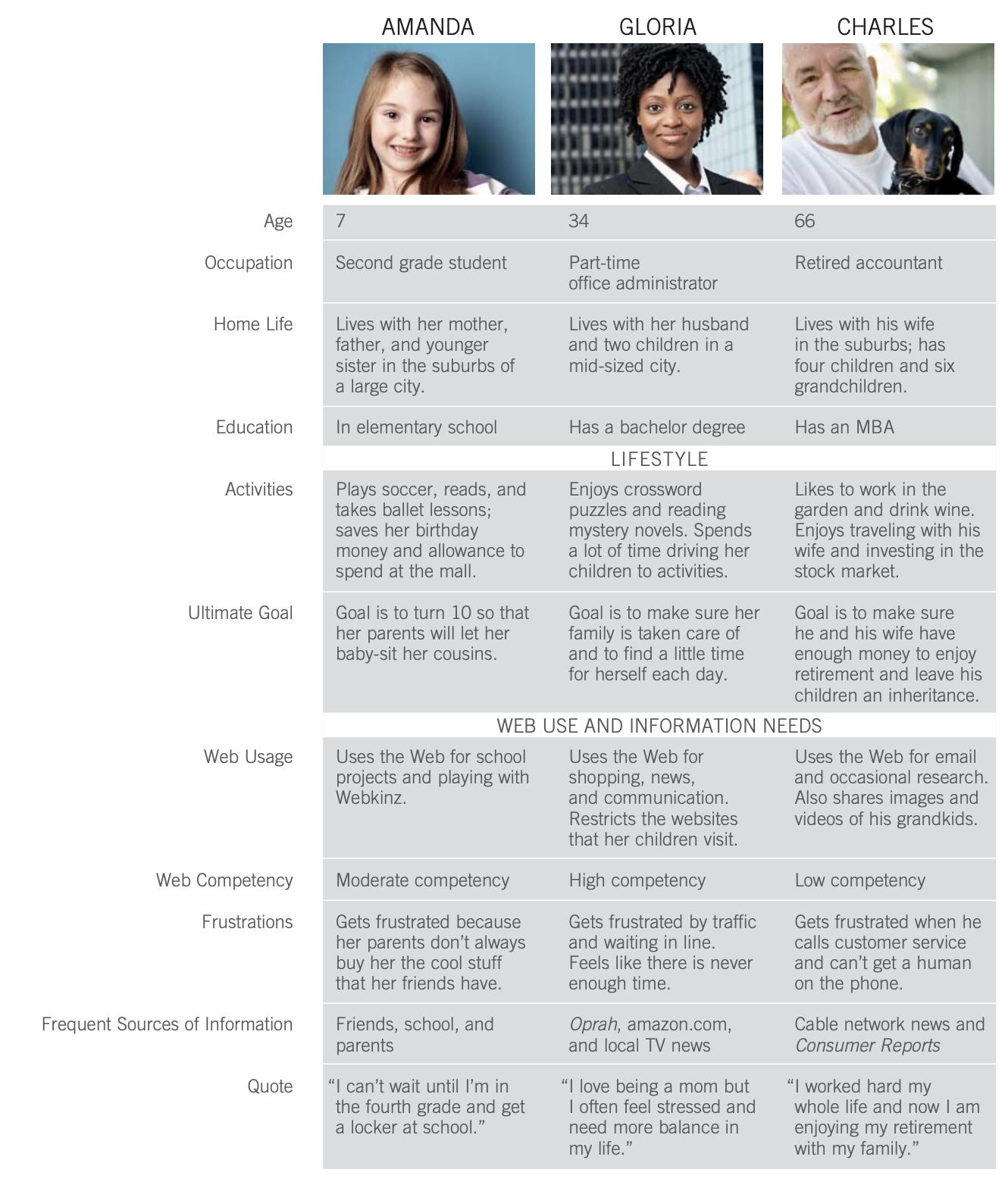

Personas: Building Points of View

This is nice because it tends to flow naturally from the user research.

When you dig deep into user research, you will start to get a picture in your mind about the user. You will probably start to see a few users emerge, with different needs. You will start to think, "some people need this, some need that." You should start to recognize that different people are using the design different ways, to do different things, and that is part of what we mean by different needs. Personas help us to recognize some of those different kinds of users, it is a pathway towards designing for a diversity of users.

Personas should never use fictional details. They are ficitonal people made of real details.

More thorough personas include photos, life details, and might be more empathic. They give you detail to dig into, they help you get to know the user's NEEDS.

"Personas" excerpt from Universal Principles of Design.

Read the full article

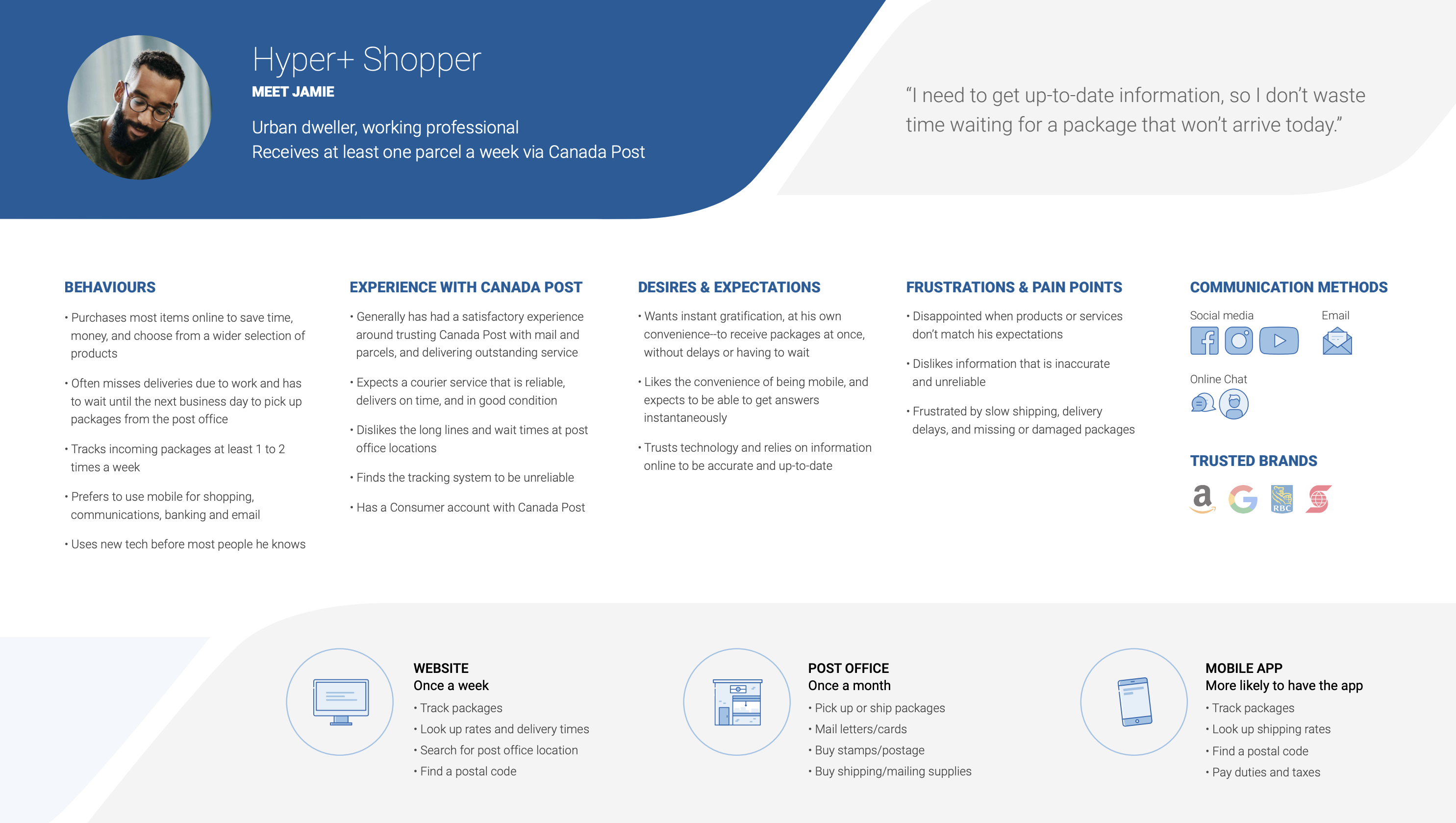

Some personas created for the Canada Postal service:

See all of them

When you take the real research data, and start to use it to create fictional users so you can get a new perspective, you have started building personas.

A simple list of personas might looks like this:

| Persona Name | Cleo | Karl | Jasmine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Cat | Human | Human |

| Age | 2-3 | 31-35 | 25-30 |

| Cat feeding behaviours | Prefers wet food. Would eat dry if starving. |

Prefers to leave a lot of cat food out so he can forget about it. | Prefers a cat food that does not have a strong odour. |

| Health | Hairballs. Vomits of overfed. Cries if underfed. |

Slight allergies. | Sleep issues related to noises. Gets unhappy if physically inactive. |

| Schedules | Up at the crack of down to have a healthy breakfast. Promptly goes back to sleep after. |

Varies depending on school schedule. Late night hours |

Regular 9-5 Sports scheduled in the evenings. |

| Education | None | College | University |

| Activities | Sleeping. Random running. Yowling. Looking out the window. |

Sleeping. Homework. Cooking. |

Nail appointments Reading Team sports with friends. |

| Ultimate Goal | To be served | To minimize effort in cat care without harming cat. | Cuddles. |

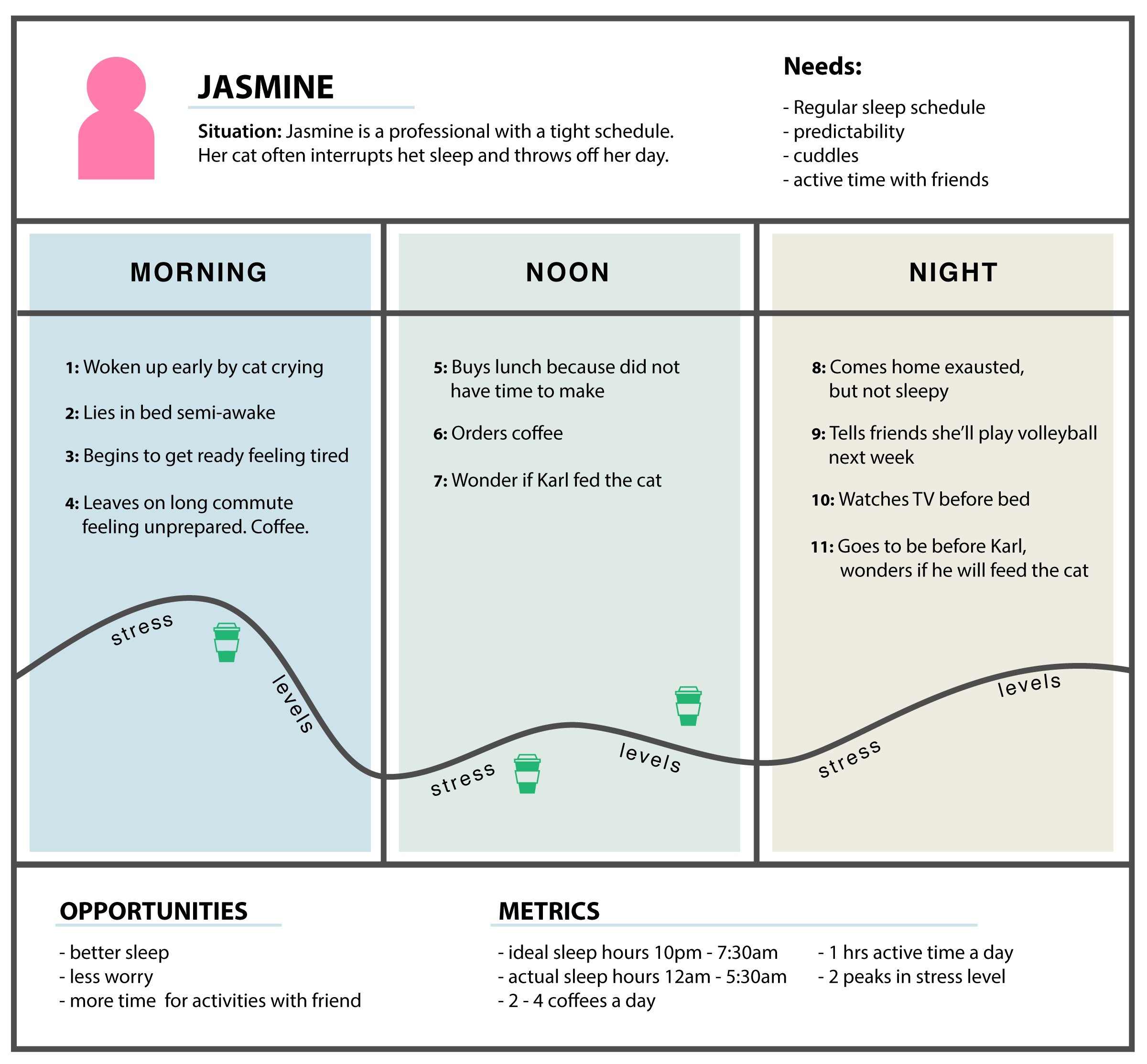

Journey Maps: Following a User

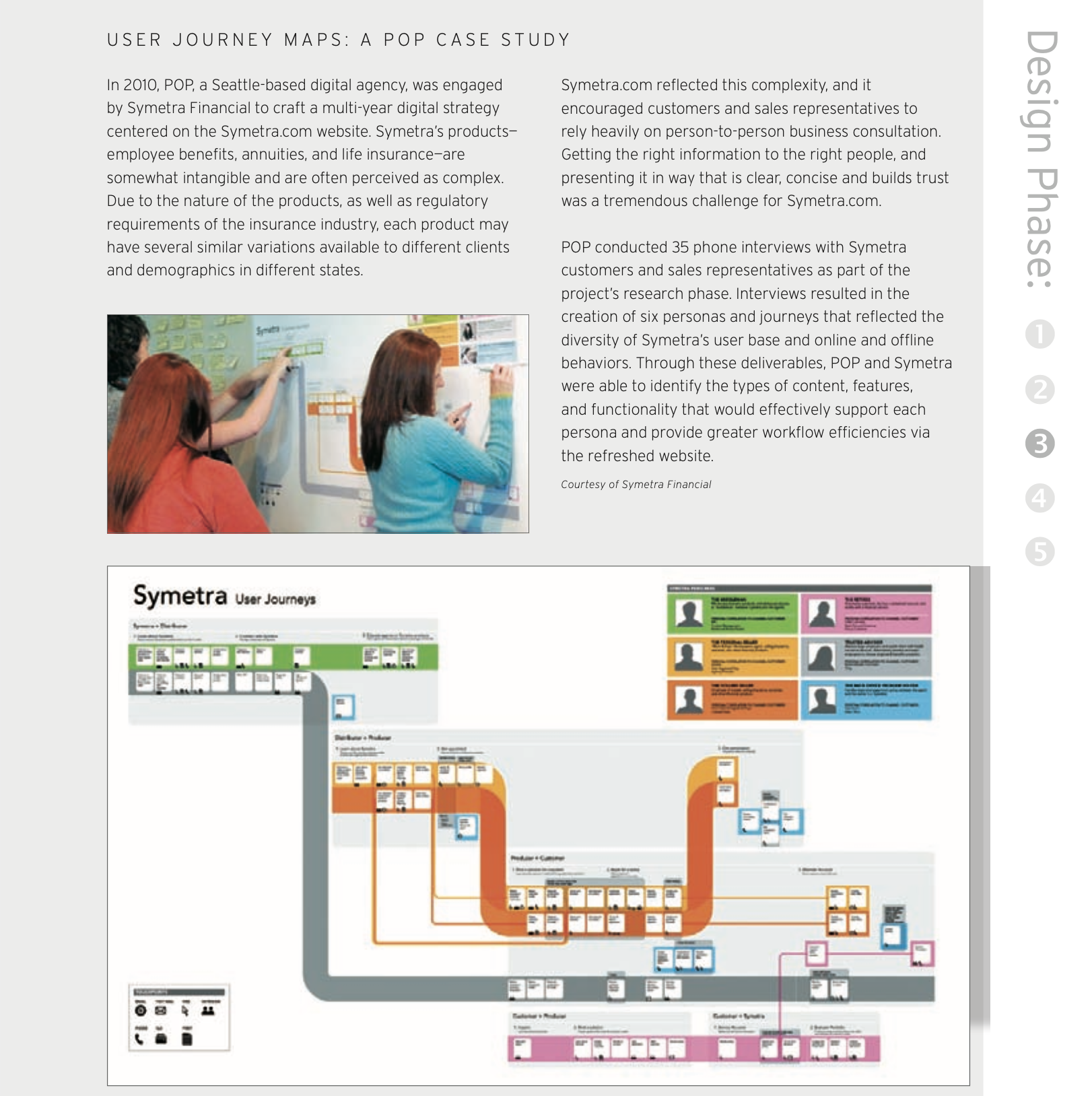

Another great way to start to define the problem is to create a journey map for your users. Journey maps go hand in hand with persona's to help the design team discuss the problem space across all users. They allow designers to see the real-world system in action, rather than a "lab" setting.

Genuine, deep, qualitative data from primary research is the only way to create engaging journey maps the reflect people's needs, feelings, and perspectives.

Showing journey maps to the user can help to refine the designer's research and make perspectives more concrete and comprehensive. Journey maps are often living documents, taped to a wall and constantly being revised as new, deeper understandings arise in the design process.

Read the full article and case study

There is no set "way" to make a journey map, but it should tell the story of a user's experience in a system, or with a design. It might be a user's entire day, it might be a 30-minute phone call with customer service, a 5-minute ordering from a cafe, and it might be the application process for college spanning months.

Some things to take note of:

- activities

- timelines

- emotions

- motivations

- wins

- opportunities

- metrics

- needs

Here is a journey map for Jasmine:

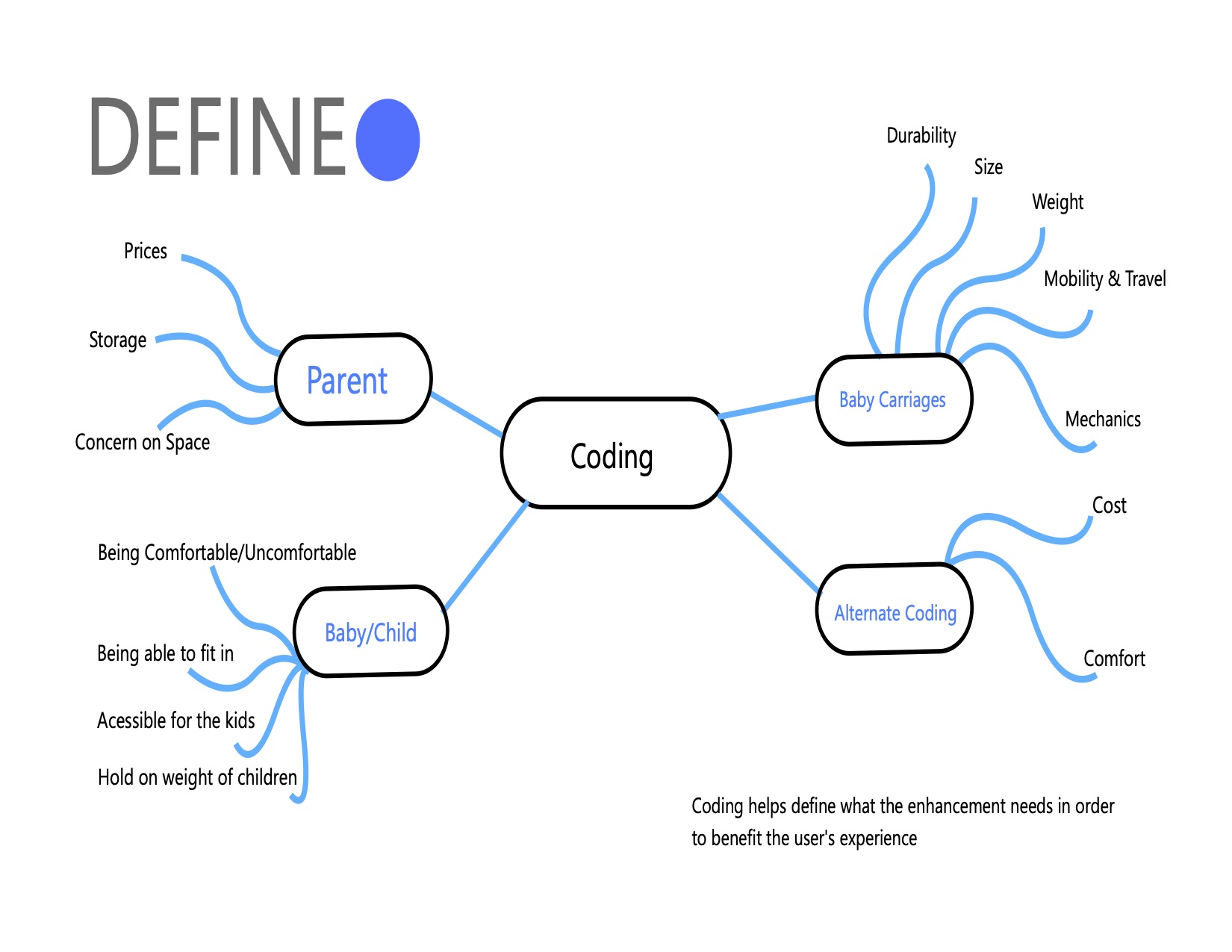

Coding

Another way to start to build a perspective from which the frame the problem space is called "coding."

Coding comes to the design world from the social sciences. It was devised in the 1960s and made famous by Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin as part of a research heuristic called "Grounded Theory."

Grounded Theory in Practice, 1967

by Anselm Strauss and Juliet Corbin

You don't need to read this book to understand coding.

Coding is a systematic way to approach qualitative data.

We "code" qualitative data (comments, emotions, cultural bahaviours, preferences...) by placing common themes into categories. The ides is that helpful patterns will emerge. Patterns that narrow in on a problem space and a new perspective.

I have coded the data as follows:

pink = Food

green = Sleep/Schedule

blue = Comfort/Discomfort

| Name | CLEO | Karl | Jasmine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Cat | Human | Human |

| Age | 2-3 | 31-35 | 25-30 |

| Food preferences | Prefers wet food. Would eat dry if starving. |

Prefers to leave a lot of cat food out so he can forget about it. | Prefers a cat food that does not have a strong odour. |

| Health Issues | Hairballs. Occasional binge eating leading to vomiting. |

Slight allergies. | Sleep issues related to noises. Gets unhappy if physically inactive |

| Schedules | Up at the crack of down to have a healthy breakfast promptly goes to sleep after |

Varies depending on school schedule. | Regular 9-5. |

| Education | None. | College | University |

| Activities | Sleeping. Random running. Yowling. Looking out the window. |

Sleeping. Random running. Yowling. Looking out the window. | Nail appointments reading team sports with friends. |

| Ultimate Goal | To be served | To minimize effort in cat care without harming cat. | Cuddles. |

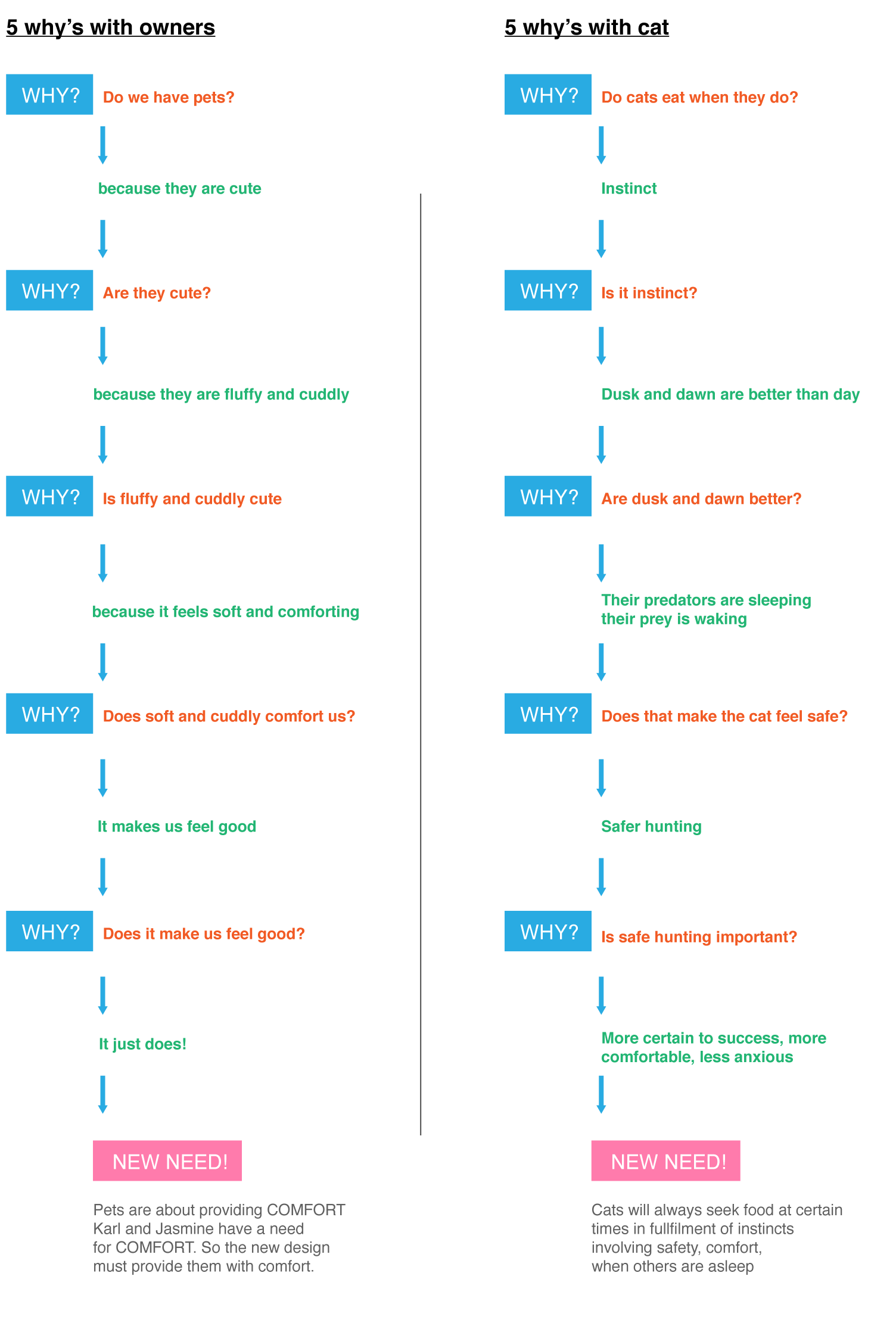

The Five Whys

Another interesting way to define a problem and re-frame it is the Five Whys method. Designer and users sit down, and continually ask "why" a design exists. The goal is to identify the causes, not the symptoms, of user's frustration with a design. And even though we say there are "5" why, you can use as many as you need.

With the Five Whys, you are trying to get to the heart of the matter. You are trying to get a new perspective on a design and change it on a fundamental level, a level that truly speaks to needs and goals, rather than on a purely aesthetic or symptomatic level.

Here we are learning that comfort, safety, schedule, are all related user needs. The design must satisfy those needs.

It is very important to reach out to a wide audience when using the the Five Whys. This is because small groups often don't have the knowledge or imagination to really narrow onto the root causes of a design failure. Another possibility is that a given link in the chain of "whys" might branch off. For example, two users could have distinctly different needs from a design, and therefore, they deepest "whys" becomes unrelated. No problem, just branch off the whys!

The problem space

Now that I knows my users, and can state their interconnected needs, I can define the problem space.

With the problem space defined through user needs, I can start to define the problem statement, the "how might we?"

I started with:

how can we increase sales of our catfood?

But that was a dead end for the imagination. So then I got to:

how can we get cats more interested in our food?

When that failed to create new ideas, it became:

how can we get people to want to buy our food for their cats?

Now I am starting think,

How can I make a food that brings regularity to schedules?

How can I make a food that makes cats quiet?

How can I make a food that stops cats from vomiting?

How can cat food become something associated with getting sleep rather than losing it?

How can cat feeding be easier for owners

How can feedings become someting cats are calm about, and feel assured of with needing to ask?

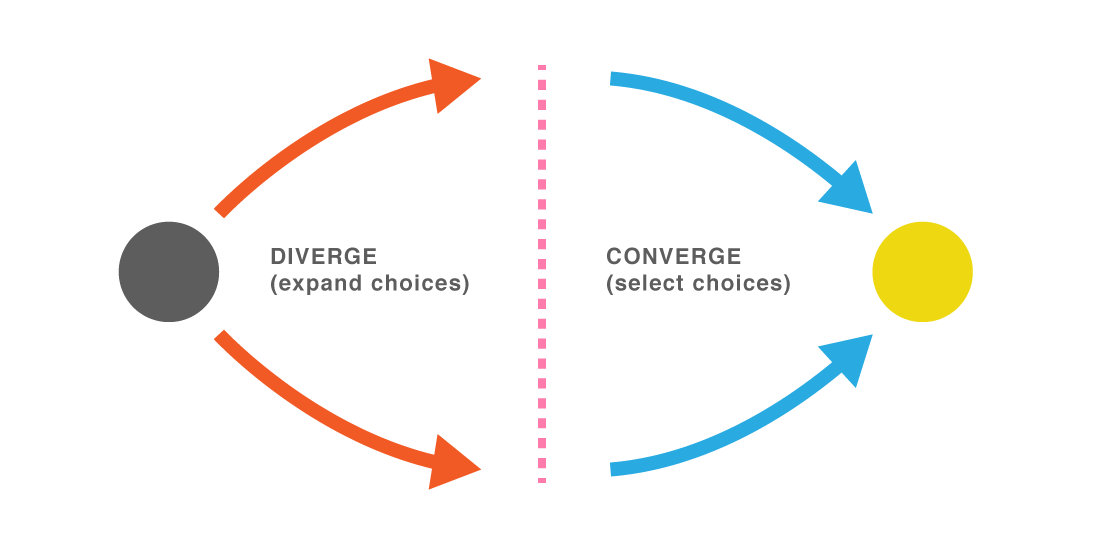

Remember this?

We just did the diverge part. Now we need to converge.

How about I give it a shot,

How can a cat food be part of reducing owners' and cat's anxiety levels?

Do you think that sort of reframes the problem space? What else might?

I would verify the coding with the users. I would check to see if the cat's eating habits is a scarcity instinct similar to anxiety (this is not proven in the existing coding). But I have a thread to pull, I have a new perspective. A new problem space.

More Coding Examples

Here is a creative coding web that some previous students created:

You can see the coding I did in grad school. Page 120, Appendix A.. I was coding from hours of video footage, interviews, and photography taken at a woodworking camp for blind woodworkers. Eventually I found that I had organized it into fundamentals of design practice.

The Next Perspective?

Remember the Earthrise image and how it gave the earthlings a new perspective? 30 years later we recieved a new photo of the Earth taken by the Voyager 1 space probe from 6 billion kilometers away.

The problem was redifined once more

"Pale Blue Dot"

by Voyager 1

Getting "the problem statement" is the goal of the empathize and define stages. In practise, be flexible. Situations change and new knowledge arrives at all stages in the game.

The other side of the coin is that design is often a business, a commodity. We need to present our ideas with confidence. We need to finish one project and move to the next. For that reason, sometimes we might take the best answer we get, knowing it might not be the best answer out there.