Introduction to Design Thinking.

And Step 1: Empathise

Five Steps in Design Thinking:

Empathize

Test

Empathize: Engage the user and find out what they need to do.

Creating helpful designs means learning who our users are (or aren't). The process of leaning this is called empathy, and it means engaging users in meaningful, open ended dialogue about their goals. Think of empathy as data with a human dimension.

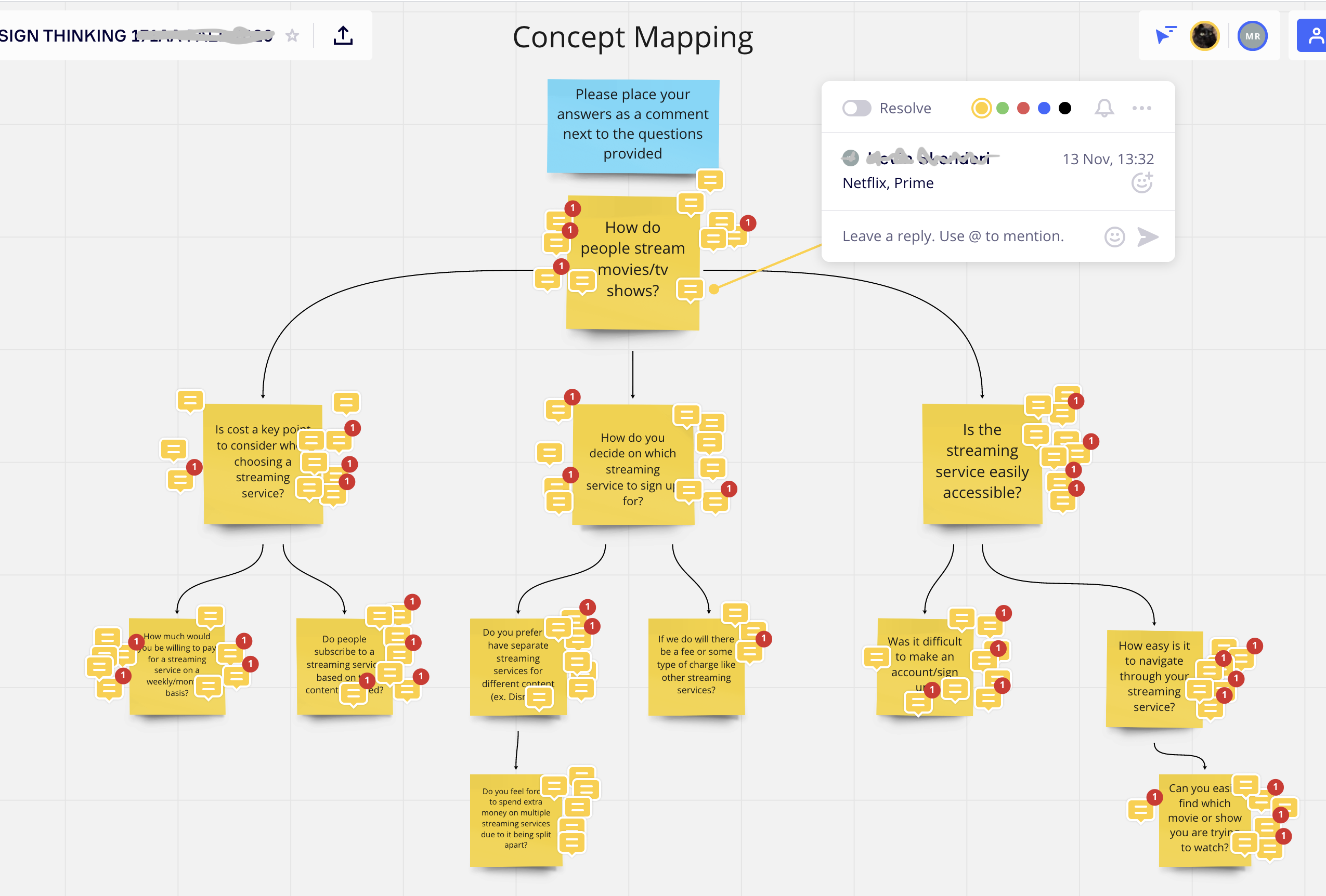

Define: What do users need, and how might we provide it?

As you build "empathy-data" you will start to understand what user needs are not being served by existing designs. Those unserved needs are called "the problem space." Once we define the problem space, we can write a problem statement that asks "how might we satisfy user needs and allow them to achieve their goals?" (but by specific).

Ideate: Challenge Assumptions and Create Ideas

You understand the user through Empathy. You used that knowledge to Defined user needs and goals into a problem statement. Now you need to come up with ideas to solve that problem, ideas for a design that lets users achieve their goals and satisfy their needs.

Prototype: Start to Create Solutions

Once you come up with ideas, you need to communicate them to the user for testing. Prototypes can take many forms, but a prototype is anything representation of your idea that user can interact with. It can be sketches, drafts, mockups, or nearly complete renders.

Test: Try Your Solutions Out

Once you have a prototype, send it to the user for testing. Design Thinking is an iterative process - so remember, you are not trying to validate your prototype and ideas. You are just seeing how the user reacts to it, and then repeating the whole 5-step process over again.

Hover for explanations

These five steps are generally what get puts forward as "the" stages of design thinking. But there are many variations of design thinking, going by different names, with different goals, and underpinned by different theoretical assumptions. They have varying focus, emphasis, guiding principles, and domain applications.

Perhaps the five steps are complete, perhaps they are not. Can you think of anything that is missing?

It's less of procedural "steps" and more like dance steps

Move the mouse around to see what it is like trying to follow the steps in order every time.

Today we are looking at Empathize and how we can use this stage to help define the problem.

origins of design thinking

A Better Mousetrap

In the age of consumerism, some thinkers have noted that design has been reduced to making incremental improvements. By that I mean, designers tend to think about how we can make a slightly more comfortable car. A slightly faster car. A slightly less expensive car. A slightly more efficient car. Eventually, we hope to produce a cheap, fast, comfortable, efficient car. We have had 100 years to do that. How are we doing?

Credit: Shutterstock

Design can re-shapes landscapes

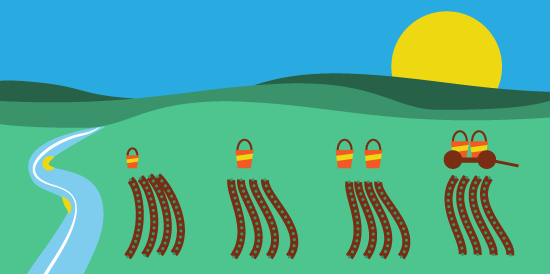

Design serves human need. Let's think about one of the most basic human needs: food. Historically, humans ensured food security by positioning themselves close to a food source. Rivers are a source of crops, livestock, and fauna, so many early settlements were beside rivers.

No matter how close you are to the river, you need a bucket to get water to your farm. The farther you are, the longer it takes to get water, which means you will get less water to your farm every day. If you get a bigger bucket, you can bring more water each time, and close the gap. At some point you will need two buckets. Then you will need a faster way to transport those buckets. Each is an incremental improvement, because the designers are stuck inside a paradigm.

Bigger buckets are incremental improvements, but where is the new idea? Where is the design thinking?

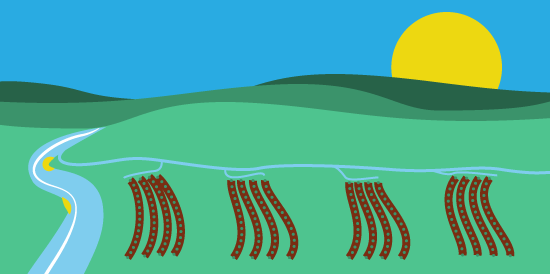

Design thinking is about identifying the solutions from outside the paradigm. Sometimes this means rephrasing the problem. Instead of asking "how might we bring water to our farms?" someone asked "how might water come to our farm on its own?"

The designers were stuck in a paradigm

This is was a paradigm shift. People were no longer working to improve the existing system. It was a whole new system, a whole new way of thinking. It made cities possible. It gave people free time.

Irrigation was a solution completely unrelated to buckets. It changed the landscape. It was a new paradigm.

Finding solutions from outside the system:

You might have heard "think outside the box." And sometime you even hear people say "there is no box." Ask yourself if that is really true. Are we really totally free and able to consider all possibilities? Do our minds truly have unfettered access to all possibilities, without barriers?

Can we easily see answers from outside the system if we are inside the system?

Design thinking is an explorative process that hopes to find the answers that are outside, and might upend, the system. To that end, we need to define the problem, to define a problem space so we can outline a solutions space

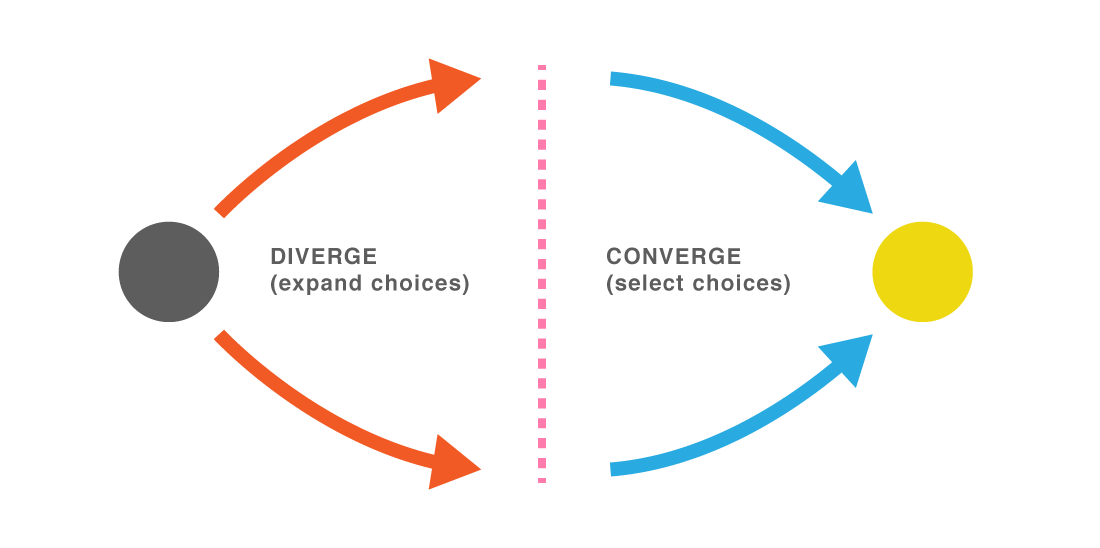

If we move away from existing choices to find new choices, we can choose things that nobody has considered before.

Finding that Innovation Sweet Spot

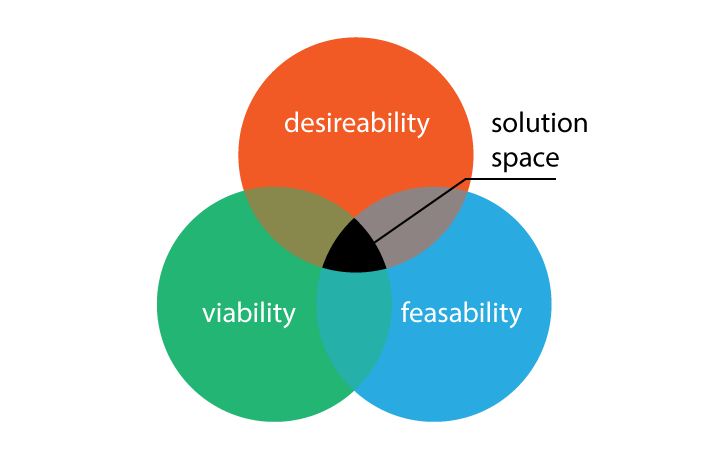

So you found a solution from outside the system. How can you ensure it will not be rejected by that system? The model below concept comes from business, but it applies to design.

Concept: Roger Martin, UofT.

Graphic: Eric Forest

- Desireability (human):

- do people want it?

- can people use it?

- does it fulfill a need?

- Viability: (business)

- does it align with business goals

- will it make money?

- Feasibility: (technology)

- how long will it take?

- can the organization implement it?

- does the technology exist, or can it be developed?

CASE STUDY

PillPack

00:07 All you have to do is tear and take your next dose. 00:10 Managing your medication has never been easier. 00:14 Here's how it works: Each month, we'll sort your meds, 00:17 including any vitamins and OTCs, into easy-to-open packets. 00:22 Need other items, like inhalers, creams or testing supplies? 00:25 We can send those too. 00:26 We'll work directly with your doctors and insurance to resolve any issues. 00:30 We'll adjust your medication if your prescriptions change. 00:33 And we'll automatically handle all of your refills so you never have to worry. 00:37 If you have questions or need to make an update, 00:39 our pharmacists are available 24/7. 00:42 Getting started is easy. 00:43 You'll need your insurance information and a list of current medications. 00:47 From there, we'll handle the rest. 00:50 We'll verify your account and transfer your prescriptions to our pharmacy. 00:54 You'll receive your first package in just a few weeks. 00:57 Now, you'll never sort your pills, 00:59 never stand in line at a pharmacy, and never miss your medication again. 01:03 It's your medication, made easy.

Discussion:

Rather than trying to make individual parts of the system just a little bit better, PillPack found a solution space that had entirely new components. The designers asked themselves:

What were some of the existing systems that they rejected and, and what was new?

remote printing, removed the pill box, no patient sorting, monthly refills, removed responsibility from the patient, increased doctor-pharmacist connection, no travelling to the pharmacy, unified source, insurance on file, increased communication options with pharmacist, reframed the over-the-counter vs. prescription difference from the customer's standpoint. In short, this is a new system altogether. They didn't think about taking something and making it work for people. They thought about people, and made something that works for them.

Empathize:

The first step in Design Thinking.

I know I said that design thinking has no order. But it usually does start with building designer - user empathy. In design, empathy means that the designer and the user can truly understand each other. To be empathetic means building a genuinely comprehensive picture of the user's needs and world.

The process of building empathy is in many ways synonymous with defining the problem.

Empathizing with strangers is hard

It's not that we are all mean robots. It's that we are really not that good at understanding each other. Author Malcolm Gladwell explains why:

So what can we do?

Gladwell suggests that we talk to strangers with "caution and humility." When we are trying to Empathize with people as designers, this is how we need to be. It is an open minded, assumptions free posture that allows for new ideas.

talk to strangers with caution and humility.

There are a few ways to do this. Below are not the only ways. They are some ways to help you build a picture of what is important in being an empathic designer and why:

- Lose your ego: You are an expert. But you are not the expert in someone else's life, or their needs. Don't let what you know get in the way of what you can learn.

- Listen: Take time to formulate your opinions. Don't build a picture of the situation too quickly. Design takes time.

- People Watch: Just look at what people do. Write it down. Explore.

Imagine if the quote below was about designers instead of poets:

The poet's eye, in fine frenzy rolling,

Doth glance from heaven to earth, from earth to heaven;

And as imagination bodies forth

The forms of things unknown, the poet's pen

Turns them to shapes and gives to airy nothing

A local habitation and a name.

Such tricks hath strong imagination,

That if it would but apprehend some joy,

It comprehends some bringer of that joy;

- Midsummer Night's Dream

SOME EXERCISES TO BUILD EMPATHY:

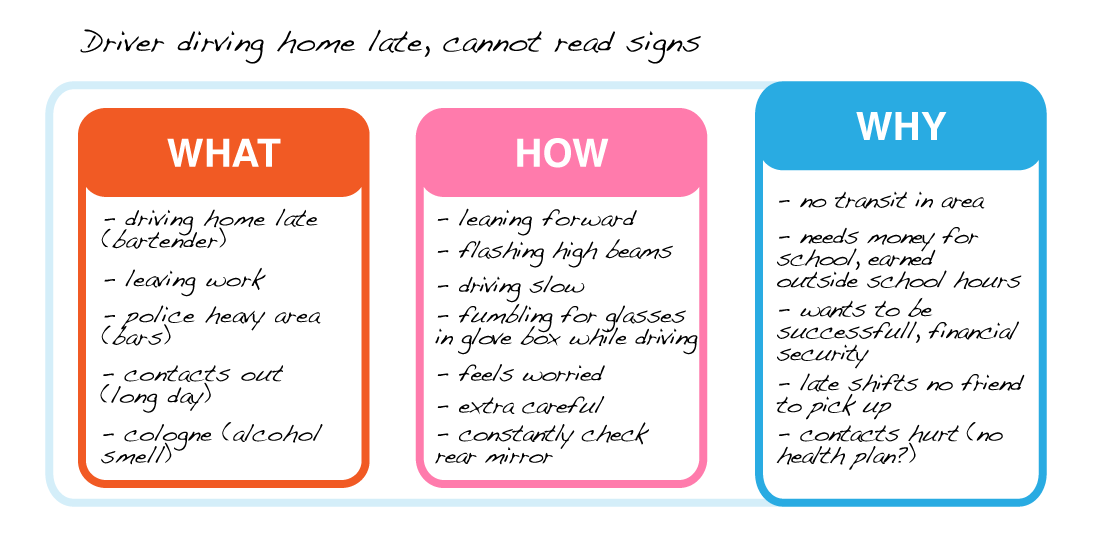

The WHAT, HOW, WHY method:

Sometimes designers like a little more structure. You can follow the What, How, Why method. Interview and observe a user, writing down notes. This method can be used for groups, individuals, and corporations. In the example below, we are looking at a bartender who uses corrective lenses and is driving home at night.

Notice how the "WHY" circles everything. Why might that be?

If we want to change the system, and find the new solution spaces rather than the incrementally better spaces, should we intervene in the what, how, or why?

- What: What is the user trying to do? Use concrete adjectives and be specific. What is going on when they try to do it - is it noisy, is it raining, is it nice out, are they alone, are they with someone?

- How: How is the user doing what they need to do? How do they look while they do it (happy, frustrated, concentrating)? How is the user managing with/without tools? How do they feel? How is their experience unique? How are they set apart as a user? How are they outside the system?

- Why: Why does the user need or want to do what they are doing? "Why" is the ultimate goal. Why is the fundamental motivation.

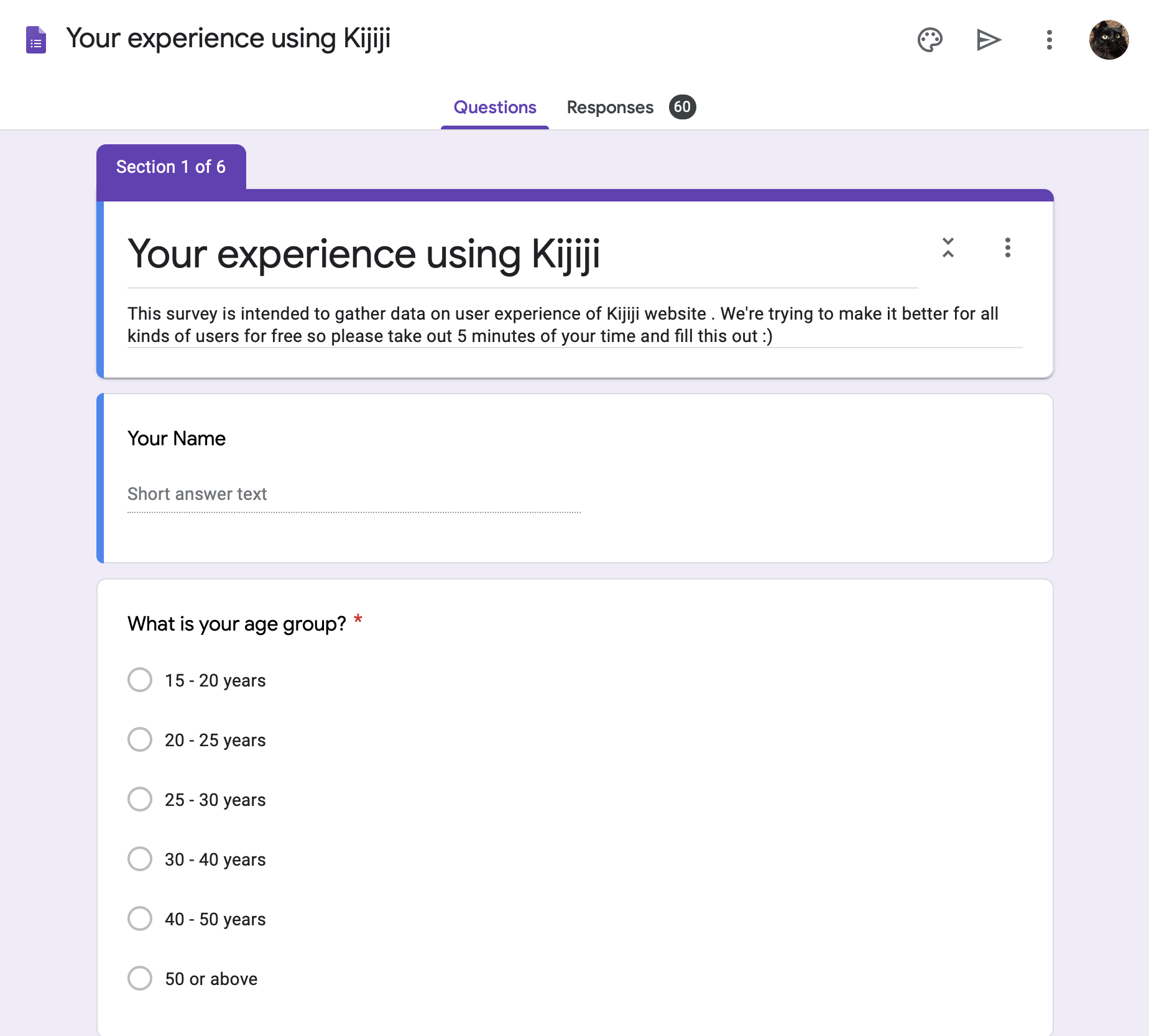

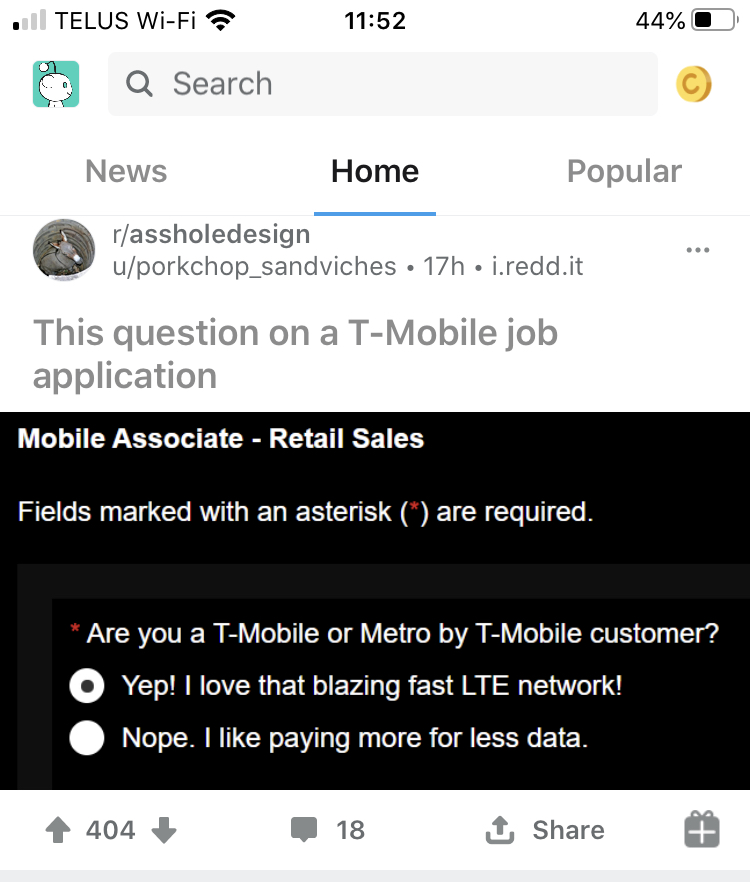

Surveys

Surveys can be a great way to gather data. But they an also mislead the designers and anger the user if the designers are not careful and caring when writing the questions.

You can create and circulate you own surveys easily with Google Forms.

A poorly written survey will not just miss important things, but it will provide false data. Consider these common "survey sins":

- False choice: These force the respondents to validate ideas that they might not actually accept. For example,

President Trump was:

Sometimes this is called a "leading question" or a "force."

1) a great President

2) the greatest President. - Forced Answers: This happens when a respondent is forced to answer a question they don't have the knowledge to answer.

- Complex Questions: Do not ask two questions are once. For example:

How would you rate the experience and value of online learning?

The value, and the experience, are two separate things. This question forces you to score them the same when it might not be. - Missing Questions: A respondent cannot answer the questions you don't ask. They may have a desire to comment on something, but the survey writer never provided the opportunity

close ended questions helps us reach a point, open ended questions gives us more viewpoints.

- Indranil Datta

What is wrong with this survey question?

In this clip from Friends, two people commit many of the "survey sins."

Surveys: Quantitative and Qualitative

You should mix quantitative and qualitative questions in your surveys.

Quantitative Questions:

Numbers such as age, or time, or how often you visit a webpage or store is quantitative data. A Likert scale is another quantitative data tool.

- No Like

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- Like

This Likert scale rates how much someone likes something on a quantitative scale of 1-5.

Quantitative data is useful, but it rarely gives the complete picture. The scale above does not tell us why the user does or does not like something. It could also be the case that the user finds the question impossible to answers. For example, maybe sometimes they would score a 5, but other times, a 2. Should the survey respondent average it out to a 3.5?

Qualitative Questions:

If you ask someone to provide a Quantitative question, always give them a chance to explain with a qualitative answer. For example, follow up a Likert scale question with "why did you score what you scored?"

Qualitative questions do no need to be linked to a quantitative question.

A table for clarity:

| QUALITATIVE | QUANTITATIVE |

|---|---|

| Words | Numbers |

| Meaning | Behaviour |

| Specifics | Generalizations |

| Deep | High level |

| Open ended | Closed ended |

| Colour, feel, smell, emotion, perception, impression | Length, duration, cost, age, speed, time |

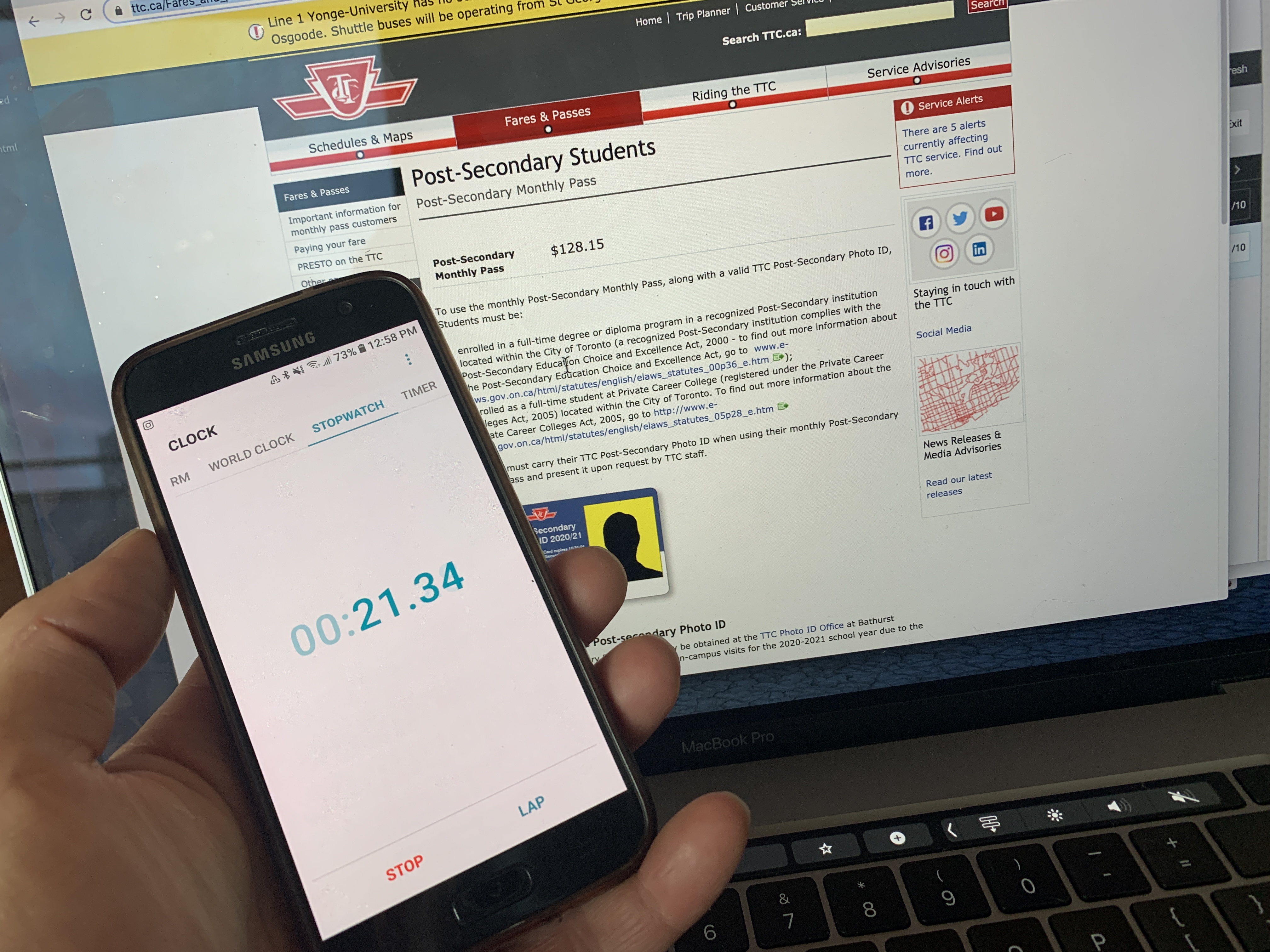

Time to Complete a Task

Another way to build empathy and better understand the user is to give users a task. Once your participants complete the task, ask them how long it took, and how they felt. The point is not to see who wins the "race." The point is to use the difference in time as a way to identify different approaches and as about those differences.

A simple example might be:

Please go to the TTC webpage and find the information page for getting a Student TTC Transit pass.

A more complex example might be:

Please go to the TTC webpage and find the information page for getting a Student TTC Transit pass. Write down where you need to go to get the ID, what you need to bring with you, and if your school is eligible.

And a even more interesting way to phrase this might be to split users up between to different webpage. For example, TTC and MiWay:

Please go to the TTC or MiWay webpage and find the information page for getting a Student TTC Transit pass. Write down where you need to go to get the ID, what you need to bring with you, and if your school is eligible.

Talk to your participants afterwards. Ask them things like:

- Which page did you visit?

- How long did it take?

- How did you go about getting to the page? (google? direct to page?)

- Mobile, desktop, or tablet?

- Do you take transit?

- What was unexpected?

- Overall impressions?

Keep in mind that faster or slower is not necessarily good or bad. We are just trying to learn what we can. We are just trying to understand the user's experience. We are just trying to Empathize.

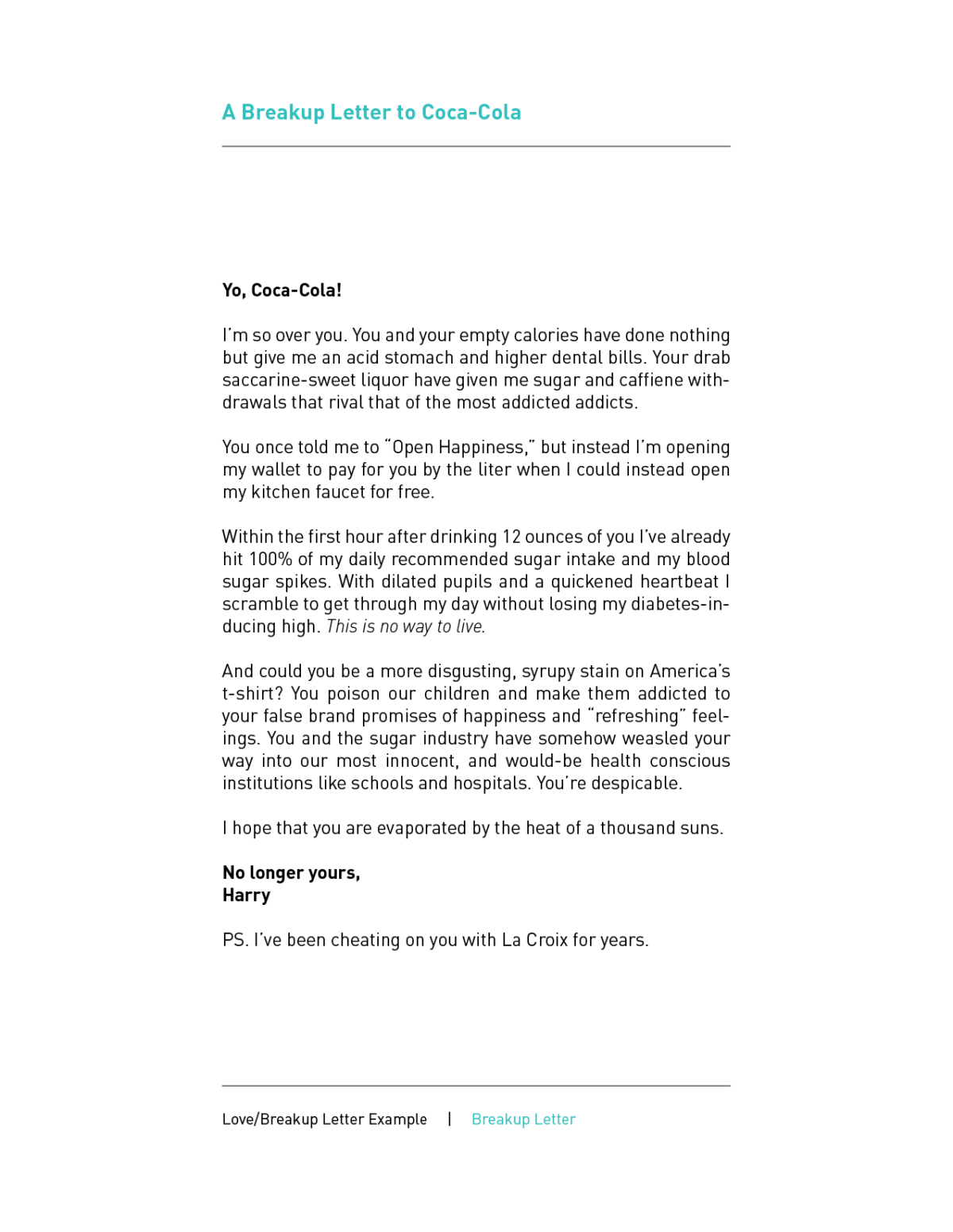

Love Letter, Breakup Letter

The love letter, and its counterpart, the breakup letter, are two methods that allow people to express their sentiments about a product or a service using a medium and a format that are immediately understood. Instead of writing to a person, however, participants are asked to personify a product and write a personal message to it. The results are often unexpectedly deep and revealing about the relationships people have with the products and services in their lives.

The love letter gets at the heart of what people feel during those magical moments of connection with a product. Descriptions of what elicits delight, infatuation, and loyalty are common themes. As researchers, you will hear about what those first moments of connection are like, and insights into why people stay with a product, even as other products compete for their attention.

The Breakup letter alternatively provides insight about how, when, and where a relationship with a product turned sour, and can be used to gain insight into why people abandon a brand or a product. People will share information about what new product they are now happy with, and what the new product has that the abandoned product does not.

These can work in groups, or with one person as a time.

Couples counselling letter

Create you own methods!